|

|

| |

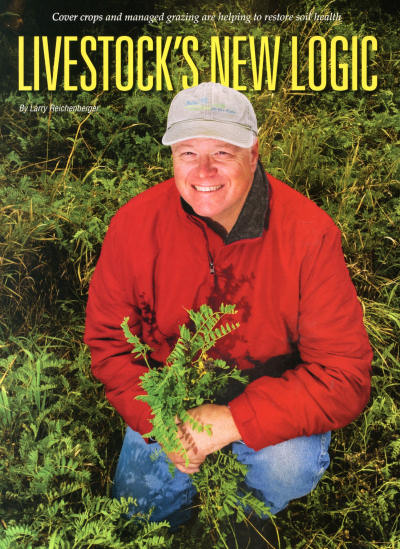

| Bismarck, N.D., farmer Gabe Brown says no-till and diverse cropping solve problems by improving the health of his soil. | |

ivestock are doing a whole lot more than lifting mortgages these days. Thanks to some innovative grazing techniques, they're also improving soil health, reducing crop inputs, protecting the environment, and easing farm transitions. This approach may seem old-school, but integrating crops and livestock into a balanced, sustainable farming system suddenly is new again.

ivestock are doing a whole lot more than lifting mortgages these days. Thanks to some innovative grazing techniques, they're also improving soil health, reducing crop inputs, protecting the environment, and easing farm transitions. This approach may seem old-school, but integrating crops and livestock into a balanced, sustainable farming system suddenly is new again.

| |

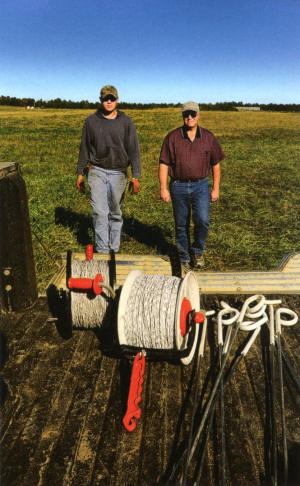

| Cattle "mob" graze paddocks of cover crops and tame grass pasture for only a few hours before time- release gates allow them to move again. | |

|

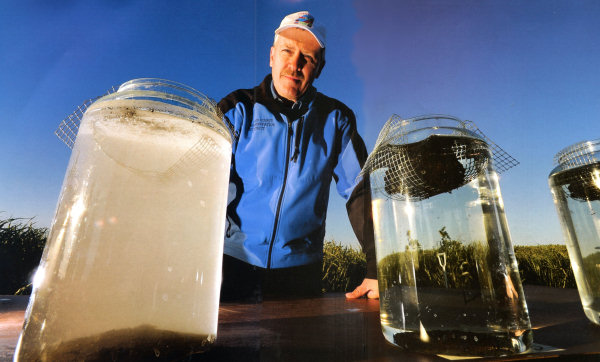

| Jay Fuhrer uses a "slake" test, where soil samples are suspended in jars of water, to show stable structure of healthy soil (at right). |

| |

| Gabe Brown (right) and son Paul use electric fence to divide cover crop fields into small paddocks for intensive rotational grazing. |

utchinson, Kan., beef producers Jim and Torrey Ball have toured Brown's ranch and believe cover crops fit in their grass-fed beef operation. "We're trying to use cover crops to improve soil health by increasing organic matter levels so we can reduce the use of fertilizer and herbicides," Jim explains.

utchinson, Kan., beef producers Jim and Torrey Ball have toured Brown's ranch and believe cover crops fit in their grass-fed beef operation. "We're trying to use cover crops to improve soil health by increasing organic matter levels so we can reduce the use of fertilizer and herbicides," Jim explains.